“I like to tell people that tae kwon do literally saved my life.”

— Kellie Thomas

Kellie Thomas, Tae Kwon Do Instructor

Story, photos and video by Cat Cutillo

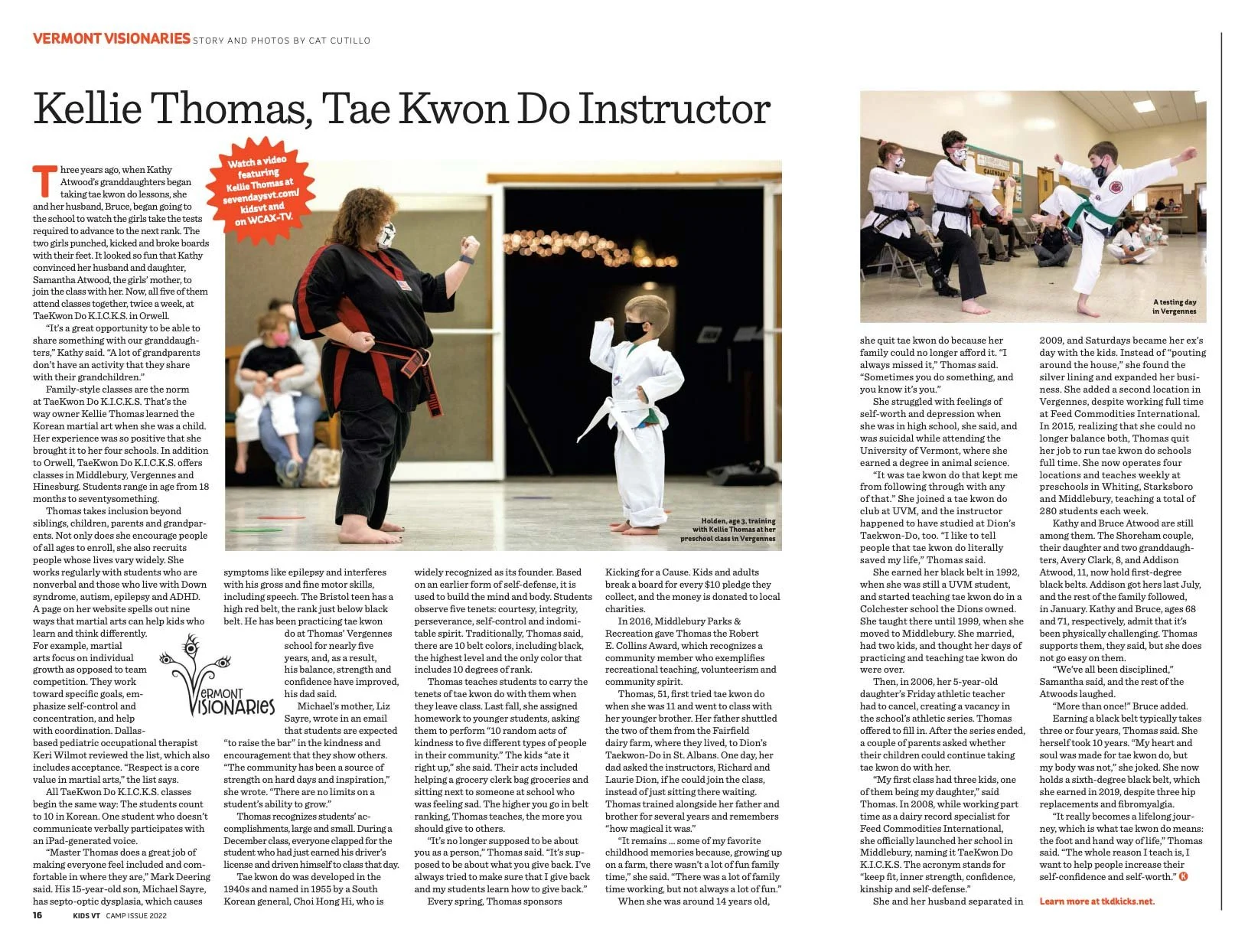

Three years ago, when Kathy Atwood's granddaughters began taking tae kwon do lessons, she and her husband, Bruce, began going to the school to watch the girls take the tests required to advance to the next rank. The two girls punched, kicked and broke boards with their feet. It looked so fun that Kathy convinced her husband and daughter, Samantha Atwood, the girls' mother, to join the class with her. Now, all five of them attend classes together, twice a week, at TaeKwon Do K.I.C.K.S. in Orwell.

"It's a great opportunity to be able to share something with our granddaughters," Kathy said. "A lot of grandparents don't have an activity that they share with their grandchildren."

Family-style classes are the norm at TaeKwon Do K.I.C.K.S. That's the way owner Kellie Thomas learned the Korean martial art when she was a child. Her experience was so positive that she brought it to her four schools. In addition to Orwell, TaeKwon Do K.I.C.K.S. offers classes in Middlebury, Vergennes and Hinesburg. Students range in age from 18 months to seventysomething.

Thomas takes inclusion beyond siblings, children, parents and grandparents. Not only does she encourage people of all ages to enroll, she also recruits people whose lives vary widely. She works regularly with students who are nonverbal and those who live with Down syndrome, autism, epilepsy and ADHD. A page on her website spells out nine ways that martial arts can help kids who learn and think differently. For example, martial arts focus on individual growth as opposed to team competition. They work toward specific goals, emphasize self-control and concentration, and help with coordination. Dallas-based pediatric occupational therapist Keri Wilmot reviewed the list, which also includes acceptance. "Respect is a core value in martial arts," the list says.

All TaeKwon Do K.I.C.K.S. classes begin the same way: The students count to 10 in Korean. One student who doesn't communicate verbally participates with an iPad-generated voice.

"Master Thomas does a great job of making everyone feel included and comfortable in where they are," Mark Deering said. His 15-year-old son, Michael Sayre, has septo-optic dysplasia, which causes symptoms like epilepsy and interferes with his gross and fine motor skills, including speech. The Bristol teen has a high red belt, the rank just below black belt. He has been practicing tae kwon do at Thomas' Vergennes school for nearly five years, and, as a result, his balance, strength and confidence have improved, his dad said.

Michael's mother, Liz Sayre, wrote in an email that students are expected "to raise the bar" in the kindness and encouragement that they show others. "The community has been a source of strength on hard days and inspiration," she wrote. "There are no limits on a student's ability to grow."

Thomas recognizes students' accomplishments, large and small. During a December class, everyone clapped for the student who had just earned his driver's license and driven himself to class that day.

Tae kwon do was developed in the 1940s and named in 1955 by a South Korean general, Choi Hong Hi, who is widely recognized as its founder. Based on an earlier form of self-defense, it is used to build the mind and body. Students observe five tenets: courtesy, integrity, perseverance, self-control and indomitable spirit. Traditionally, Thomas said, there are 10 belt colors, including black, the highest level and the only color that includes 10 degrees of rank.

Thomas teaches students to carry the tenets of tae kwon do with them when they leave class. Last fall, she assigned homework to younger students, asking them to perform "10 random acts of kindness to five different types of people in their community." The kids "ate it right up," she said. Their acts included helping a grocery clerk bag groceries and sitting next to someone at school who was feeling sad. The higher you go in belt ranking, Thomas teaches, the more you should give to others.

"It's no longer supposed to be about you as a person," Thomas said. "It's supposed to be about what you give back. I've always tried to make sure that I give back and my students learn how to give back."

Every spring, Thomas sponsors Kicking for a Cause. Kids and adults break a board for every $10 pledge they collect, and the money is donated to local charities.

In 2016, Middlebury Parks & Recreation gave Thomas the Robert E. Collins Award, which recognizes a community member who exemplifies recreational teaching, volunteerism and community spirit.

Thomas, 51, first tried tae kwon do when she was 11 and went to class with her younger brother. Her father shuttled the two of them from the Fairfield dairy farm, where they lived, to Dion's Taekwon-Do in St. Albans. One day, her dad asked the instructors, Richard and Laurie Dion, if he could join the class, instead of just sitting there waiting. Thomas trained alongside her father and brother for several years and remembers "how magical it was."

"It remains ... some of my favorite childhood memories because, growing up on a farm, there wasn't a lot of fun family time," she said. "There was a lot of family time working, but not always a lot of fun."

When she was around 14 years old, she quit tae kwon do because her family could no longer afford it. "I always missed it," Thomas said. "Sometimes you do something, and you know it's you."

She struggled with feelings of self-worth and depression when she was in high school, she said, and was suicidal while attending the University of Vermont, where she earned a degree in animal science.

"It was tae kwon do that kept me from following through with any of that." She joined a tae kwon do club at UVM, and the instructor happened to have studied at Dion's Taekwon-Do, too. "I like to tell people that tae kwon do literally saved my life," Thomas said.

She earned her black belt in 1992, when she was still a UVM student, and started teaching tae kwon do in a Colchester school the Dions owned. She taught there until 1999, when she moved to Middlebury. She married, had two kids, and thought her days of practicing and teaching tae kwon do were over.

Then, in 2006, her 5-year-old daughter's Friday athletic teacher had to cancel, creating a vacancy in the school's athletic series. Thomas offered to fill in. After the series ended, a couple of parents asked whether their children could continue taking tae kwon do with her.

"My first class had three kids, one of them being my daughter," said Thomas. In 2008, while working part time as a dairy record specialist for Feed Commodities International, she officially launched her school in Middlebury, naming it TaeKwon Do K.I.C.K.S. The acronym stands for "keep fit, inner strength, confidence, kinship and self-defense."

She and her husband separated in 2009, and Saturdays became her ex's day with the kids. Instead of "pouting around the house," she found the silver lining and expanded her business. She added a second location in Vergennes, despite working full time at Feed Commodities International. In 2015, realizing that she could no longer balance both, Thomas quit her job to run tae kwon do schools full time. She now operates four locations and teaches weekly at preschools in Whiting, Starksboro and Middlebury, teaching a total of 280 students each week.

Kathy and Bruce Atwood are still among them. The Shoreham couple, their daughter and two granddaughters, Avery Clark, 8, and Addison Atwood, 11, now hold first-degree black belts. Addison got hers last July, and the rest of the family followed, in January. Kathy and Bruce, ages 68 and 71, respectively, admit that it's been physically challenging. Thomas supports them, they said, but she does not go easy on them.

"We've all been disciplined," Samantha said, and the rest of the Atwoods laughed.

"More than once!" Bruce added.

Earning a black belt typically takes three or four years, Thomas said. She herself took 10 years. "My heart and soul was made for tae kwon do, but my body was not," she joked. She now holds a sixth-degree black belt, which she earned in 2019, despite three hip replacements and fibromyalgia.

"It really becomes a lifelong journey, which is what tae kwon do means: the foot and hand way of life," Thomas said. "The whole reason I teach is, I want to help people increase their self-confidence and self-worth."